Longevity Cities Series — Part One

Longevity is often imagined as the domain of labs, biotech startups, or Bryan Johnson–style protocols. But the most powerful engine of healthy longevity today is far older, broader, and much more familiar: The City.

Cities are where our environments, behaviors, stress levels, mobility patterns, air quality, wages, social networks, and public institutions intertwine to shape how long — and how well — we live. They are the world’s largest biotechnologies: intricate sociotechnical systems that influence health more profoundly than any available medical intervention. And they are also the primary sites where any future breakthroughs — including those that might finally push humanity beyond the Calment Limit, the long-standing world record of 122 years and 164 days — will take root and scale.

This essay introduces The Longevity City: a technoprogressive framework for remaking urban life so that cities can systematically expand the longevity dividend — the economic and social benefits that emerge when more people live longer, healthier lives.

Importantly — as Part Two will explore — this framework is not speculative. The essential components already exist in cities around the world. Our task, therefore, is not to invent a new paradigm from scratch, but to weave existing models into a coherent, longevity-focused civic architecture, and then push the conversation towards a more democratic innovation model for actualizing the next stage of breakthroughs.

This essay is a call for technoprogressives to take the lead in maximizing our longevity potential using every tool available — in the cities, towns, and regions where we already live and work. And if you don’t yet identify as a technoprogressive, consider this framework an invitation into the practical work of building a future where healthy longevity is a public good, accessible to all.

Why Cities Are the Future of Longevity

Cities regulate the primary determinants of health: air, water, mobility, social participation, safety, wages, rest, heat exposure, social networks, and stress. Modern public health emerged from cities — sanitation systems, vaccination programs, emergency medicine, public health agencies, and crisis response infrastructures.

Nearly every major improvement in lifespan was forged through urban networks of doctors, researchers, planners, labor organizers, and civic movements.

Cities remain the world’s engines of scientific and civic innovation.

If healthy longevity — or Longevity 2.0 — is going to emerge, it will follow the developmental pathways of Longevity 1.0. It will take root in the dense, collaborative, richly infrastructured terrain of the modern city.

Public Health Maximalism: A New Paradigm for Urban Governance

The foundational principle of The Longevity City is simple:

Every urban system is a health system.

Housing, transportation, wages, childcare, school quality, pollution exposure, neighborhood design, digital infrastructure — all of these shape lifespan and healthspan.

To maximize the number of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) available today, we have to treat cities as unified systems of systems — capable of fostering healthy longevity through a paradigm I call public health maximalism.

Public health maximalism reinterprets public health according to its most expansive and scientifically grounded definition. Instead of focusing only on disease prevention, it treats public health as the coordinating logic for how cities design policy, deploy interventions, and build grassroots demands.

This gives us a shared evidentiary foundation — standardized metrics rather than vague appeals to “well-being” or “flourishing.”

A few principles illustrate what this looks like:

Systems are interconnected

Transit influences pollution, which affects cardiovascular health, but it also shapes land use, mobility, stress, and economic opportunity. Small design choices cascade across systems.

Public health must be a protocol, not a department

Public health should no longer be confined to a regulatory silo. It must become the standard that governs decisions in housing, labor, transportation, climate, policing, technology, and more.

Coalitions multiply

Labor organizers, disability justice advocates, urbanists, Vision Zero campaigns, climate planners, and child- and elder-friendly city proponents all benefit from a public-health-first urbanism.

Public health maximalism creates shared terrain for powerful, technoprogressive municipal coalitions.

The Social Longevity Gap: The Crisis We Can Solve

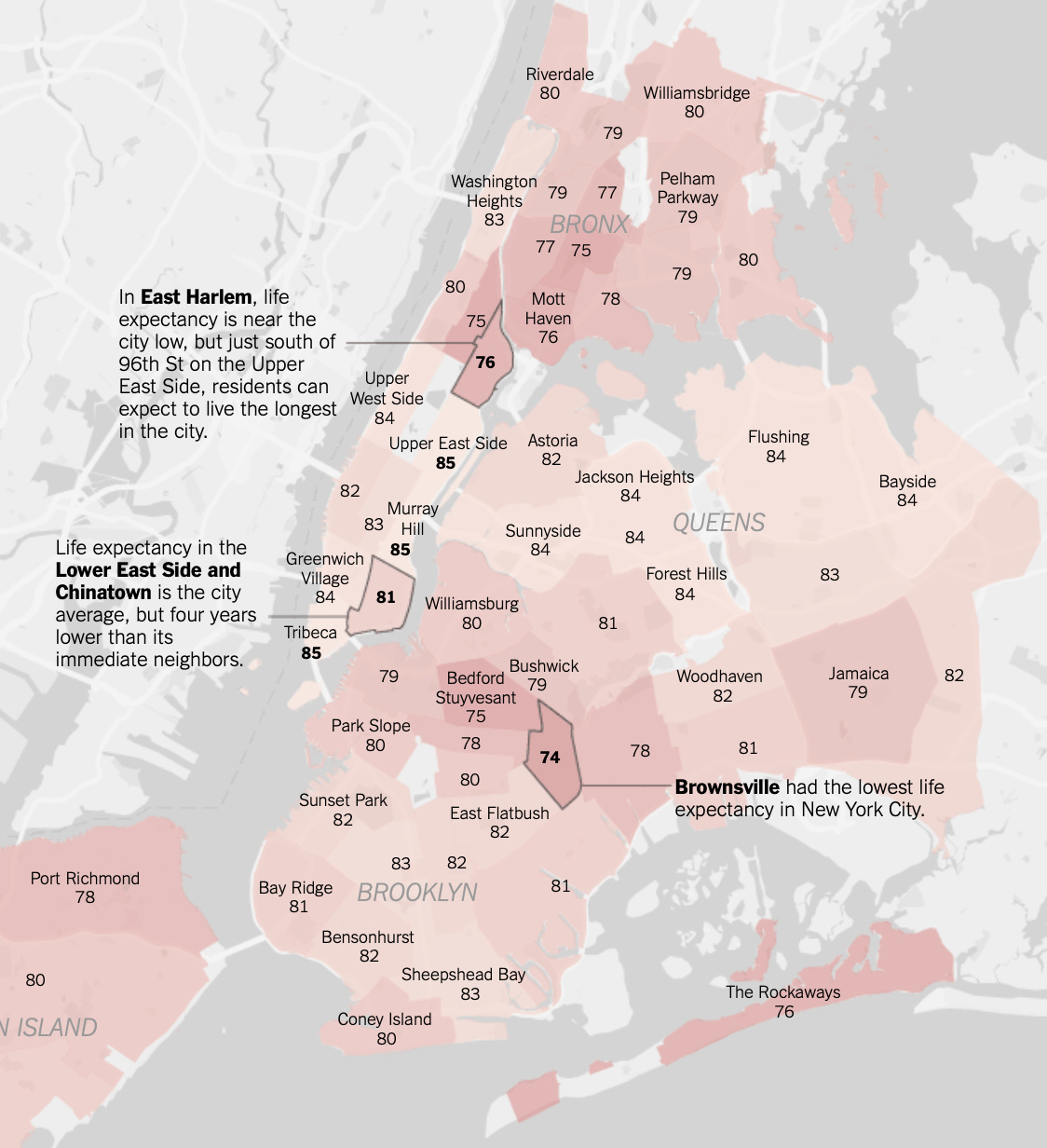

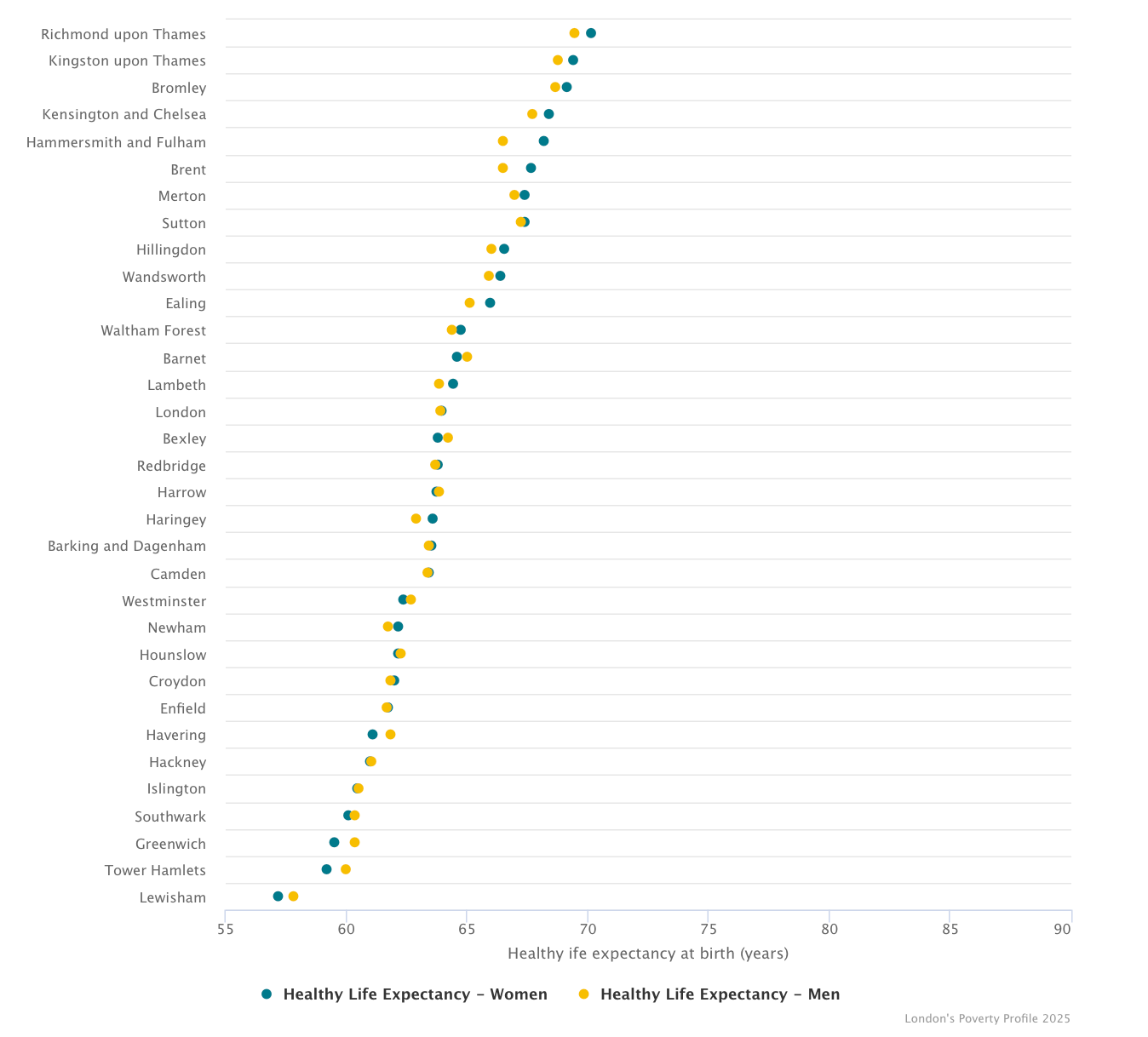

Within any metropolitan area, life expectancy often varies 20–30 years across neighborhood lines. These disparities are not genetic. They are the result of structural inequalities in policy, infrastructure, and opportunity.

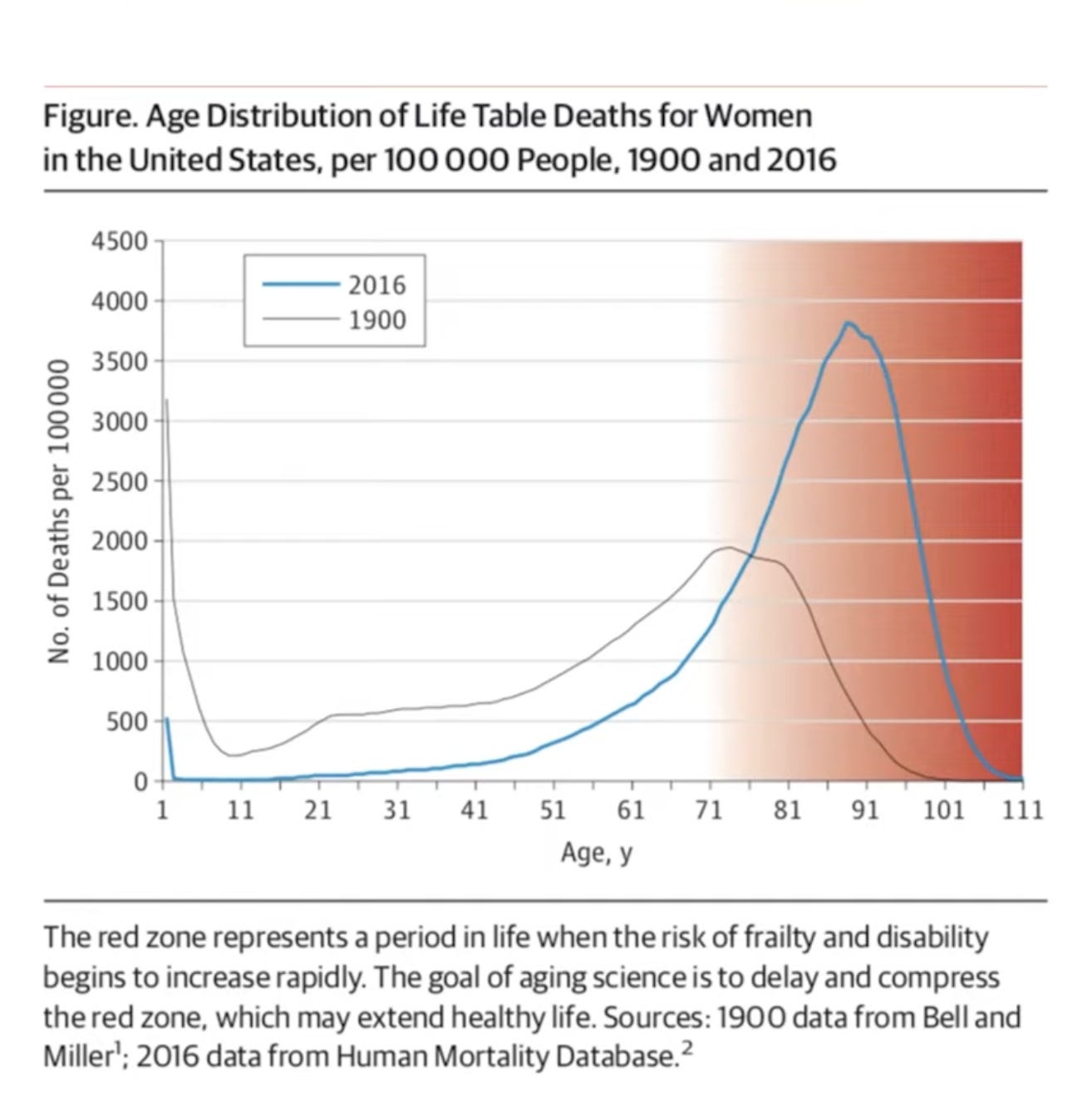

Layered on top of this is the expanding red zone — the number of years people spend alive but not healthy. Across the world, healthspan is failing to keep up with lifespan, putting immense strain on families, workers, and healthcare systems. In many countries, this divergence is becoming an existential threat to social and economic stability as populations age rapidly.

These twin crises — the neighborhood longevity gap and the healthspan gap — are among the defining public health challenges of the 21st century. Left unaddressed, they could produce catastrophic demographic pressures.

But they also reveal one of the most powerful opportunities for technoprogressive municipal governance. If cities can close these gaps — extending healthspan, reducing inequality, and compressing the red zone — they will generate enormous social, economic, and ethical dividends.

The Longevity City offers a roadmap for doing exactly that.